After a series of warm-up events over the past year, the third and final phase of the 13th Shanghai Biennale ‘An Exhibition’ finally launched last month, taking over three floors of the Power Station of Art through Sunday 25 July.

Set against the backdrop of a world that seems to be drifting apart, and yet at the same time has never been so connected, the exhibition’s central message is simple yet urgent: it’s time for human beings to connect with nature and with each other.

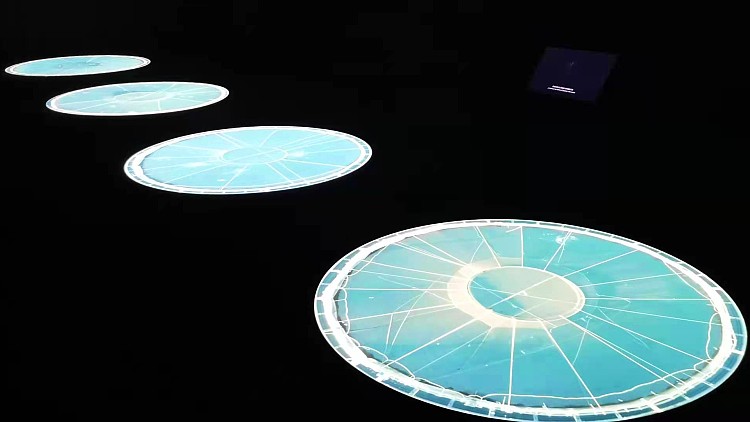

The Chief Curator Spanish architect Andrés Jaque and his all-female lineup of curators made sure the message sinks in deep. It’s a video-heavy exhibition that follows the Biennale’s over-arching theme of ‘Bodies of Water’ – an exploration of bodies that exceed humanity and ‘the fluid ways in which they infiltrate, constitute and relate to one another’ – in all kinds of ways.

Video installation ‘Traces of Escapees’ by London-based artist duo Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe studies the genetic implications of fish escapees from intensive open-net fish farms on other fish and marine life. Another video work from Spanish artist Pepe Espaliú, made in 1992 amid the AIDS crisis, portrays the terminally ill artist carried by a succession of people in pairs across a busy street in Madrid. Pu Yingwei’s ‘Dam Theatre’ explores the theme of CHINAFRICA through the story of his uncle, a Chinese hydraulic engineer who helped build dams in Kenya. It’s all about connections.

Photograph: Yu Zhiming (Cooking Sections (Collective), Salmon: A Red Herring, 2020, Removal of farmed salmon from the institution; cyclorama; powder-coated steel; silk; ETC ColourSource CYC lights; ETC Source 4 Luster 2 lights; sound (3:1 surround), Dimensions variable, 21:00 minutes, Commissioned for “Art Now,” Tate Britain, 2020)

Some works forge new connections by pushing back against old ones. Colombian artist Alberto Baraya’s categorisation of fake/plastic flowers and plants is one. The project satirises the practices in which Europeans claimed ownership over the natural resources from the ‘New World’ they ‘discovered’ and restores the indigenous narrative.

In a similar vein, films made by Karrabing Film Collective – an indigenous media group from Australia’s Northern Territory – don’t shy away from exposing ‘the longstanding facets of colonial violence that impact members directly’, such as constant harassment from police officers and housing corporations in their native land.

While China-born artist Liu Chuang’s video project ‘Can Sound Be Currency’ takes you deep into the rural terrains of western China where a large number of bitcoin mining sites are located and asks audiences to ponder the relationship between technology and ecological intelligence.

The largest display is Cecilia Visuña’s ‘Quipu Menstrual (Shanghai), (2006/2021)’ – you can’t miss it once you reach the vast space on the second floor. It’s a massive installation consisting of streams of blood-red wool suspended from the ceiling to the floor. Also from Visuña is a short video (one that gives us the most hope of what art can achieve) of her protest performance at the foot of the Andean mountain El Plomo in 2006 against a proposed mining project that would destroy three glaciers for gold. It was filmed the same day Michelle Bachelet was elected as the first female president of Chile. The mining project was dropped, and art won.

Photograph: courtesy Power Station of Art, Lehmann Maupin (New York, London, Hong Kong and Seoul) and the artist (Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu Menstrual (Shanghai), 2006/2021, Mixed media installation with unspun wool and video, Dimensions variable, 04:12 minutes)

Compared to past Shanghai Biennales, this one does feel a bit empty. You’ll find works here and there without much context to help you comprehend. But ultimately, it’s about moving away from an anthropocentric view of the world and making connections instead of setting up walls. We are all in this ‘planetary wet-togetherness’, after all.