We’re full speed ahead here in Shanghai. With the city hurtling towards the future, sometimes it’s nice to take a look back in black and white – at the bustling market that predated Taobao by a century; the wall that encompassed the ‘original Shanghai’; and the brewery that came before we were swept by the craft beer craze.

Get urban nostalgic with some beautiful archive pics, and hear the stories behind some of Shanghai’s grandest buildings and tangles of alleyways courtesy of the local experts at Historic Shanghai, Newman Tours and Shanghai Insiders.

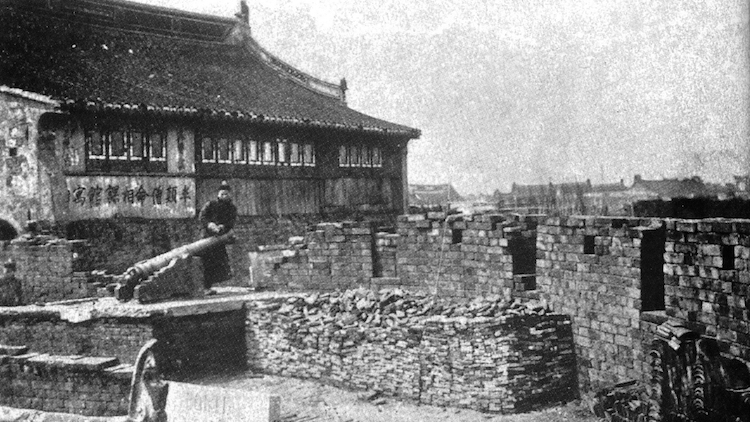

The old City Wall

Standing ten metres tall, covering five kilometres and surrounded by a six-metre deep moat, the wall that ran around Shanghai’s old Chinese city (aka ‘the original Shanghai’) was built in the 1550s to protect it from raids by Japanese pirates. The historic City Wall stood until 1912 when, after the Xinhai Revolution, the majority was knocked down upon the orders of the new governor General Chen Qimei. While the structure itself is gone, its legacy remains. You can trace its path along Renmin and Zhonghua Lus that follow its trajectory, and some of its old gate names – like Laoximen and Xiaonanmen – are still used today.

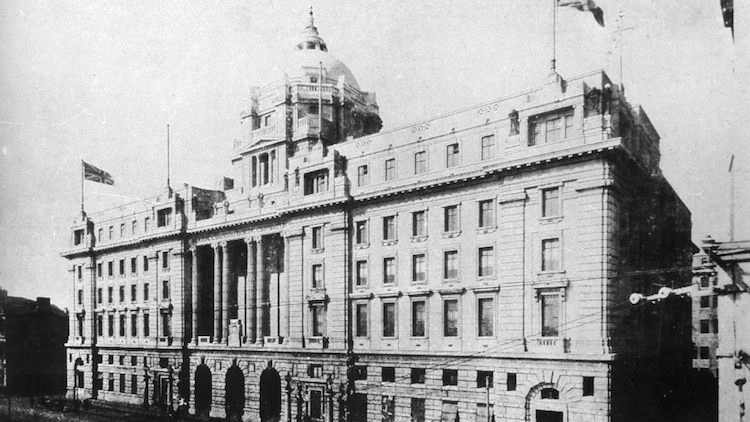

A marble monolith on The Bund

Looking something more like a cathedral than a bank, the HSBC Building was described as the greatest in Asia when it was completed in 1923. The world’s second largest bank at the time and laden with marble, the building was quite a feat for a company founded not even 60 years earlier.

Shanghai Pudong Development Bank has since moved into the Bund-side monolith – HSBC decided not to fund restoration and maintenance of its original Shanghai HQ when it was invited back to China in the ’80s. Today, visitors will still find incredible mosaics on the underside of the building’s dome, along with some of the largest marble pillars in the world.

Research courtesy Newman Tours.

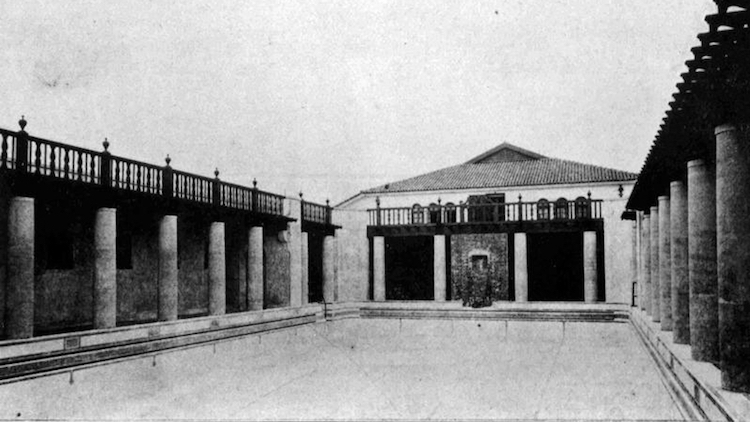

A club ‘way out in the country’

A playground for Shanghai’s American community, first founded in 1918, the American country club relocated to Panyu Lu in 1927. Set outside the International Settlement on a five-acre expanse of farmland, the area at the time was considered ‘really out in the country’, according to a guidebook from the 1930s. Designed by American architect Elliott Hazzard (also behind the former Shanghai Power Company building, now The Shanghai EDITION) the club was a space for socials, gin fizz- and whiskey sour-fuelled parties, and a lot of sport – it was even home to the city’s only open air outdoor pool.

The sprawling grounds might have been cemented over, but the social aspect of the former country club is still very much alive in its current iteration. As of last year, the renovated buildings have been incorporated into F&B and lifestyle hub, Columbia Circle. Although the former clubhouse building currently sits empty, and the pool (still with its original tiles) is off-limits for swimming, the surrounding area is buzzing with restaurants and bars, including familiar names like Pirata, Blackbird and Seesaw Coffee.

A female-run hotel for foreign dignitaries

Taken over by property mogul Victor Sassoon in the 1930s, the Cathay Mansions accommodated colonial bachelors who’d spend time just across the road at the French Sports Club (now the Okura Garden Hotel).

After 1949, the building was turned into the Jinjiang Hotel and Shanghai’s only hotel allowed to accommodate foreign guests, becoming the go-to for government leaders and foreign dignitaries. Jinjiang Hotel was helmed by the enterprising branding pro, Dong Zhujun, and ultimately borrowed her company name. After escaping years of hardship as a girl, Dong Zhujun parlayed her experience launching the popular Jinjiang restaurant and tea house, becoming one of the city’s first large-scale female entrepreneurs. Though Jinjiang is now a state-owned enterprise, Dong Zhujun’s presence can still be felt in the city, with some older generations opting for the ‘more reliable’ white Jinjiang taxis.

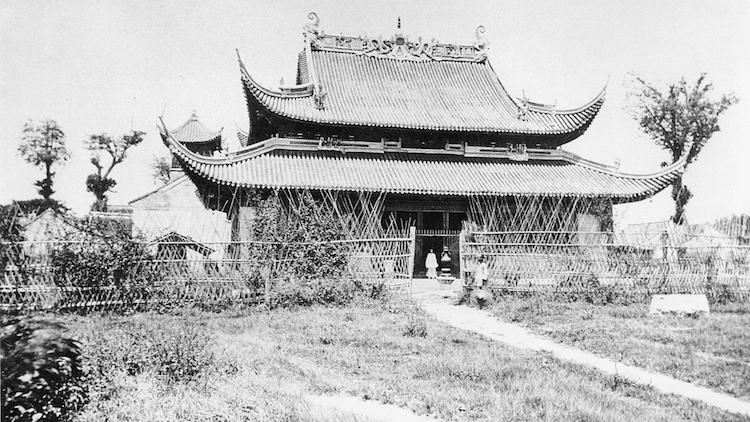

The old Jingan Temple

After facing repeated floods on the marshy lands at its original home by Suzhou Creek, Jingan Temple relocated to its current spot on what was once Bubbling Well Road (now Nanjing Xi Lu, the well for which the street was formerly named has long since been filled in) during the 12th century.

The temple has become commercialised over the course of its 700-plus-year history. But, not short on sizable donations from wealthy donors, visitors can find impressive Buddhist sculptures including an enormous camphor depiction of goddess of mercy Guanyin and a solid silver depiction of Shijiamouni, supposedly weighing 15 tons.

Research courtesy Newman Tours. For its audio guide to Jingan Temple (and more landmarks) click here.

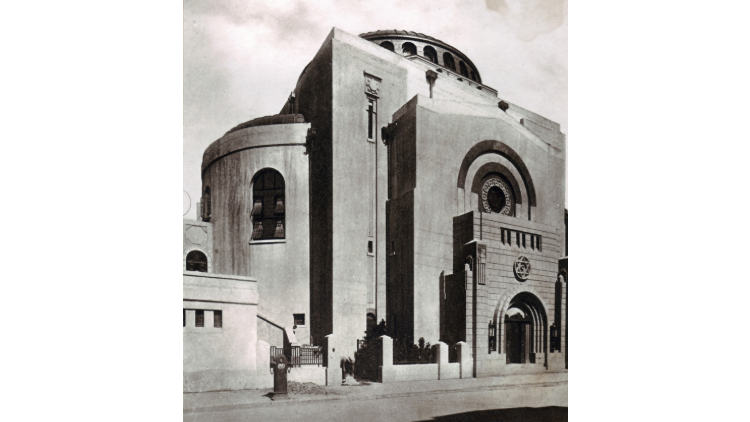

An art deco synagogue

Offering a peek into Shanghai’s past as a city with a 20,000-strong Jewish community, one of the earliest Art Deco buildings built in 1927 (even two years before legendary landmark the Cathay Hotel, now the Fairmont Peace Hotel) was the Beth Aharon Synagogue on today’s Huqiu Lu.

Funded by ‘the richest man in old Shanghai’, Baghdadi Jew Silas Aaron Hardoon – whose self-made story is itself renowned – the 400-seater Sephardic synagogue acted as sanctuary for the Mir Yeshiva during the Second World War. After 1949, the building became a part of the Wenhui Bao newspaper compound until it was demolished in 1985.

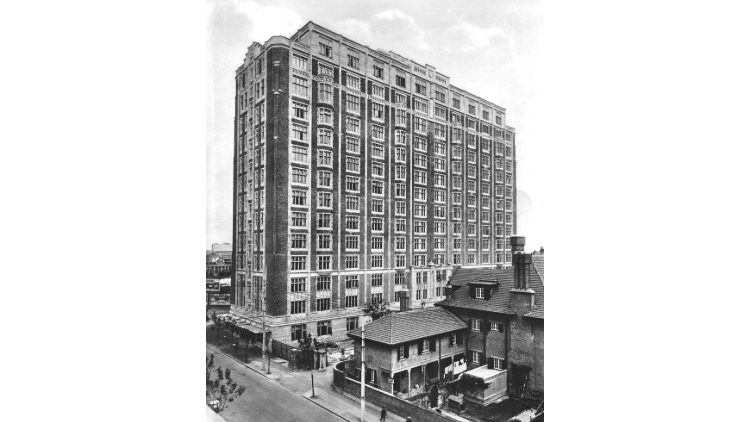

The golden oldie of international schools

This Hengshan Lu landmark (even featured in a Kodak ad in the ’40s) was the digs of Shanghai’s oldest international school through the mid-1900s. Founded in 1912 with a small campus in Hongkou, by 1917 the Shanghai American School was on the hunt for a bigger space. The founders bought a 15-acre plot of rural farmland on what was then Avenue Pétain, and made it into a sprawling campus with 300 students when it opened in the autumn of 1923. Largely serving as SAS’ Administration Building from 1923-1949, the building pictured was modelled after Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. During WWII, SAS officially shut in 1941, but the Avenue Pétain campus lived on in the form of one of three ‘bootleg’ campuses until 1949. In 1950, the school closed for 30 years.

While the Shanghai American School itself once again thrives today, its most iconic building, still easily recognisable for its distinctive cupola, is no longer open to the public. Now, it houses a state-owned research institute specialising in industrial shipbuilding equipment.

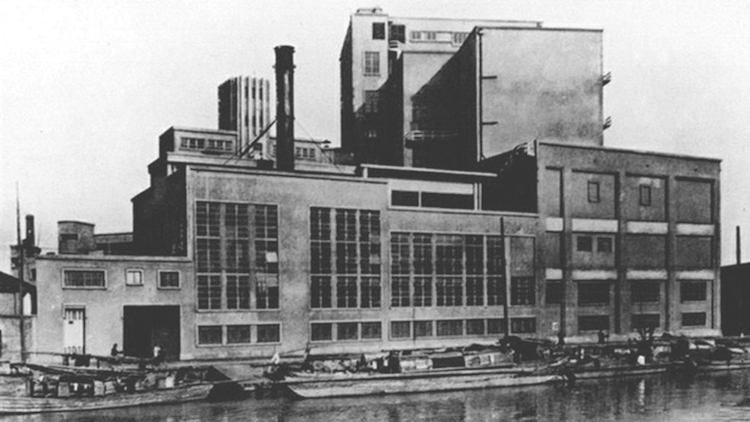

China’s biggest brewery in the ’30s

When it opened on the swampy banks of Suzhou Creek in 1936, Union Brewery produced 5 million bottles of beer yearly, making it China’s biggest. Putting a concrete structure with heavy brewing equipment on the marshy lands was no joke, with supports going more than 30 metres deep. It’s one of the only industrial buildings in Shanghai by Hungarian architect László Hudec, who designed dozens of notable Shanghai buildings (including Asia’s first skyscraper, the Park Hotel). Union Brewery was partially demolished in 2002 and remains largely unoccupied, its bottling section, brew house and office building the only three surviving structures today.

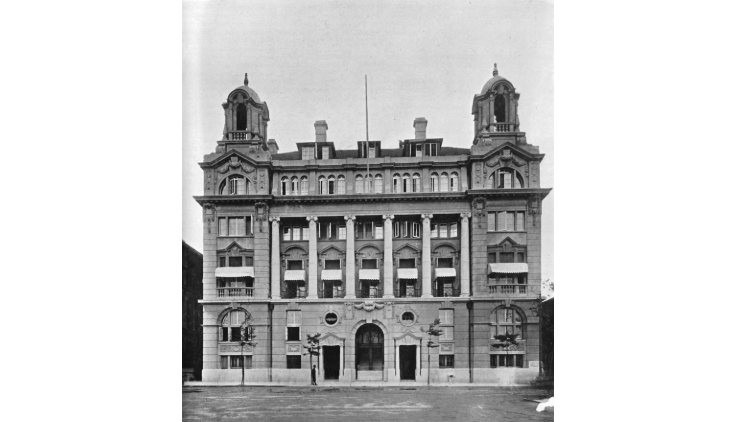

A members-only club on The Bund

Simply being wealthy and successful didn’t ensure you access to the mega-exclusive Shanghai Club in its heyday during the 1920s and ’30s; both property mogul Victor Sassoon and self-made tea tycoon Thomas Lipton were denied membership to the British gentlemen’s club.

Over the years, the historic space has served a wide range of purposes (home to the city’s first KFC, among others). It’s now home to Shanghai’s Waldorf Astoria, housing an updated version of the famed Long Bar that, clocking in at 34 metres, was once the world’s longest. Though it’s no longer a record breaker, the old-school cocktail den is still on many Shanghai visitors’ to-do list for a stiff drink and live jazz.

The bustling Sanjiaodi Market

While it’s perhaps hard to imagine a time before wet markets – a bastion of China’s social scene – Sanjiaodi Market was one of the city’s first, dating back to the 1890s. (Before wet markets, word is people would buy produce street-side.) Known amongst foreign residents as Hongkew Market, Sanjiaodi was the largest wet market in Shanghai by the time it was demolished in the 1990s to make way for an office tower.

Set in the triangular junction formed by today’s Tanggu, Hanyang and Emei Lus in Hongkou district, Sanjiaodi was a destination for locals and foreigners alike. Its neighbourhood was home to a number of Russian, Japanese and Jewish immigrants and refugees, and influenced by its cohort of international customers, the market was known for stocking hard-to-find delicacies (like Russian bread) alongside local offerings.

A progressive girls’ school from the 1800s

A progressive school for its day – when women’s education was viewed as largely unnecessary – McTyeire was founded by the South Methodist Mission in 1892 for the elite women of Shanghai. Classes, led by foreign teachers, were held in English with a Western, Christian outlook. In 1922, the campus moved from its original location on Hankou Lu to Jiangsu Lu. In 1952, it closed, merging with St Mary’s Hall to become the Shanghai No 3 Girls’ High School. Over the years, McTyeire saw some of Shanghai’s most influential women pass through its hallowed halls, including the three Soong sisters who would go on to shape modern China as we know it.

Sticking to its roots as an all-girls’ school – albeit now a state-run one – the high school is still known as a revered establishment for women (in fact it’s the only ‘key’ state girls’ school in Mainland China), from where graduates go on to study at top universities both locally and internationally. Looks-wise, two of the original ‘American Collegiate’-style buildings still stand today: the May 1st Hall (then called Lambuth Hall), and the May 4th Hall (then Richardson Hall; pictured) – on the steps outside which graduation pictures were traditionally and still are taken.

The former British Consulate building

Three years after Shanghai opened its borders to trade, in 1846 the city’s first British Consul General George Balfour bought the Li Chia Chang property to build the new British Consulate compound (it was formerly located in the old Chinese city). Located at the northern edge of today’s Bund area, the first British Consulate building on the new site was built in 1849. However a string of bad fortune saw the original collapse and the second destroyed by fire; the third and final iteration dates back to 1873. One of the oldest foreign-built buildings in Shanghai, except two breaks in 1941 and 1949, it remained home to the British Consulate until 1967.

Today, as part of the Waitanyuan development, the former British Consulate – or No 1 Waitanyuan – is now a swanky event space. Since 2017, it has been managed by luxury hotel group The Peninsula (whose Shanghai outlet sits just next door).

![How to Register Wechat Official Account Outside China [2022 Guide]](https://expats-hub-1306202437.cos.ap-shanghai.myqcloud.com/2022/05/WeChat-open-official-account-profile-300x200.jpeg)